It would be almost impossible to enumerate the many things we learn from our children, particularly those who have special needs. Infinite patience, for one. Hope. Perspective. Appreciation. Acceptance. Love. And maybe a thing or two about dinosaurs or natural disasters.

But with each of our children, special needs or not, if we really stop to think about it, we might find that one thing stands out above all else. The one thing that we really needed to learn from them, and from them alone. I wrote recently that what I have learned from Neil is the power of belief. More than anything else, every day of his life, Neil has taught me to believe. But what I have learned from Adam is just as valuable.

In a word – surrender.

We’re not conditioned to view surrender as a good thing. To most of us, it means giving up. But to me, surrender means letting go. It means letting go of that which I cannot control. It means letting go of expectations. It means accepting What Is. And it’s something that Adam, even more than Neil, has taught me every day.

*

Unfortunately, I don’t write as much about Adam. This website is called Teen Autism, and Adam was never officially diagnosed on the spectrum. He did, however, experience a significant delay in language development, necessitating speech therapy until almost age ten. But what really affected him – and still does – is his sensory processing disorder. He must have been miserable as an infant, toddler, and even a preschooler. It wasn’t until age five that he seemed to be somewhat at home in his body; he was finally talking and smiling more often than crying and yelling.

But his eating issues continued to get worse. Whereas I would call Neil a picky eater, Adam is a limited eater. A year ago, as he was nearing 13, I started to realize that it seemed to be a control issue with him – not to control me, but to have some control in his life. He couldn’t control that his dad, whom he idolized, lived 700 miles away. He couldn’t control that he had an autistic brother. But he could control the food that he decided to eat. So what started off as a sensory issue developed into something even more involved.

And it bothered me greatly, not just because I worried about his health and his growth. It bothered me that I couldn’t just cook dinner for my child and he would eat it. Even at age 13! It bothered me that he was a teenager and, like his brother, should have been eating me out of house and home (even though Neil is picky, he still manages to eat a variety of foods, and in mass quantities). And it bothered me that Adam would eat more food when he was with his father. I took him to see a counselor, and he fought me, saying, “You’re making me do something against my will!” I compromised, telling him that if he increased his dinner choices to seven things, one to rotate each day of the week, that we would stop going to the counselor. He reached that point within three weekly sessions, and although I followed through, he has since lapsed to five or six items on the rotating dinner menu.

So I surrendered.

I let go of my expectations about Adam’s eating habits. I let go of my expectations about how he responds to having an autistic brother (hint: it’s not always noble or gracious; in fact, usually not). I had to surrender. I had to. And I thought that if he could spend more time year-round with his dad that he might start eating better when he’s with me, too.

*

He has been with his dad for over three weeks now. I’ve talked to him several times, and the last time I did he told me, with excitement and pride in his voice, “I’ve been trying lots of new foods, Mom! I’ve been eating a lot.” And I told him, choking back tears, that I was so glad to hear it.

And someday soon I will tell him that there is nothing I wouldn’t have done to help him to be as happy and healthy as possible. I will tell him that it’s okay that he’s not always glad to have an autistic brother, that I honor his feelings. I will tell him that I accept the fact that he eats differently. And I will tell him that I have become a more balanced person because of it, because of learning to surrender.

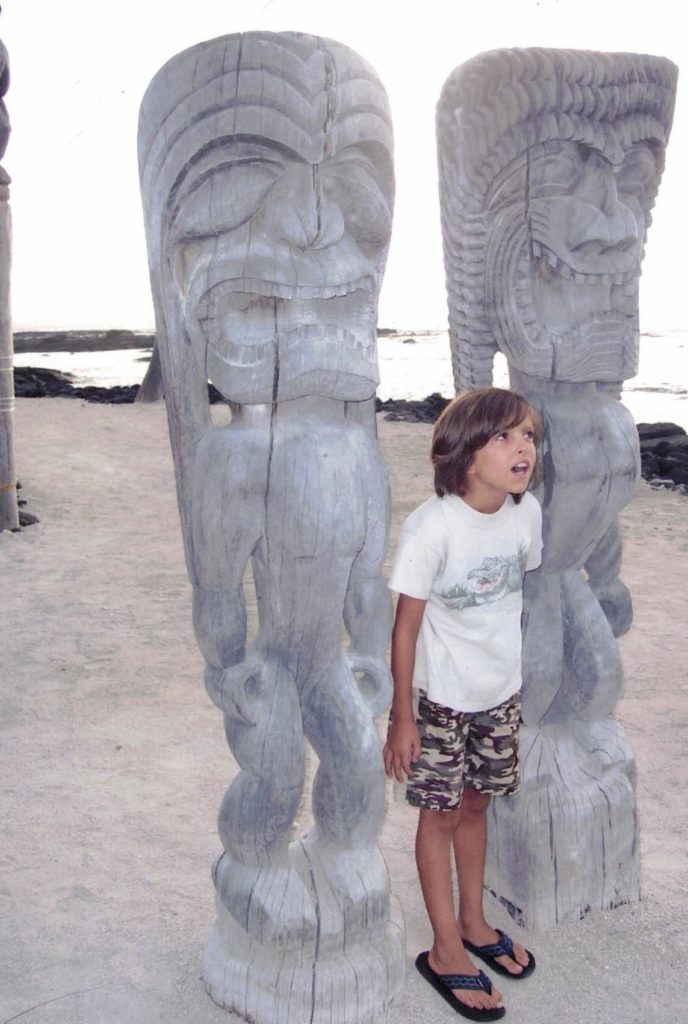

Adam, age 9, being a tiki at Pu’uhonua National Historical Park, Hawaii, 2006