When Nigel was 4-5 years old and not yet functionally verbal, he wanted so badly to play with the kids he would see at our local playground, but of course, he did not know how. I, preoccupied with toddler Aidan, would often have to intervene when Nigel would go up to a boy about his age and get in his face and start laughing. Nigel observed that when children played together, they would laugh, but he seemed to think that the laughter came first, that laughter would result in playing, and more laughter. Unfortunately, his tactic only resulted in the other kids getting either sad or angry – because they thought that Nigel was making fun of them. I would rush over and say, “He’s not making fun of you. He’s laughing because he wants to play with you,” but the negative impression had already been made, and they would leave. Nigel couldn’t ask me what he had done wrong. If I tried to explain it to him, he wouldn’t have understood. The only thing he understood was laughter. Laughter meant playing. Laughter meant fun.

These days, Nigel understands much better how to approach his peers. He understands that in order to laugh with people, you have to start doing a fun activity first. Or – you can watch a funny movie together. And Nigel has discovered that this is the easiest way to achieve the laughter connection that he has craved all of his life.

I don’t remember how old he was the first time I watched a Peter Sellers/Inspector Clouseau movie with him. All I remember is how much he loved the fact that everyone watching was laughing together, which I’m sure gave him a sense of security and completeness. Later, not only did he have a new source for his echolalia, he had a new response from his audience. He discovered that if he randomly dropped a line from one of those movies that he wouldn’t be told “Let’s not say things from movies.” No, he realized, the magic of saying something from a funny movie is that people will laugh.

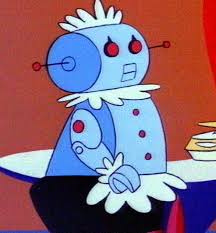

Over the years, he has branched out with his funny movies – got into The Three Stooges of course, and then the iconic Monty Python. He enjoyed some Saturday Night Live episodes, especially those featuring Chris Farley. It seems that slapstick appeals to him most, to his kinesthetic sense of processing. But the old Inspector Clouseau movies featured both slapstick and verbal comedy, so he could experience the best of both worlds with those. He could walk into a room, and in Clouseau’s nasally voice ask, “The wax?” and then slip on his feet and say “AAAAHH!” as he fell to the ground, and everyone would laugh. When saying goodbye to someone, he could salute and say, “Until we meet again and the case is sol-ved,” causing more laughter. He could express his frustration with doing chores by imitating Clouseau’s boss, Chief Inspector Dreyfus, and say, “I’ve had enough!” and has also been known to say, “Somewhere, over the rainbow” in a crazy voice while on the verge of a meltdown, just like Dreyfus did in the insane asylum. He has definitely used movie echolalia in a variety of situations.

And in doing so, Nigel has finally mastered a way to meet his need for communal laughter. It’s been many years since he laughed in someone’s face to get them to laugh with him. What’s really great is that he’s discovered he can make people laugh just as much when he says his own funny lines. One day last week, he tripped over something, bumped into me, and caused me to knock over a glass of water. With each bungle he said a quick, “Sorry,” and, with the last one, looked at me to check my response. I couldn’t help but smile. It was all too funny – the tripping, the bumping, the sorrys, the spill – just like a scene out of a movie. Then, smirking, he said, “I’m getting more Clouseau-ish by the minute!” and we both collapsed on the floor in laughter.