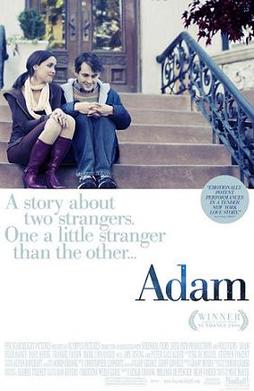

Ever since the movie Adam came out on DVD, I’ve debated watching it. I was curious but skeptical. I wondered how realistic it could be, or how stereotypical, how formulaic, or how Hollywoodized. I feared that it might be contrived, either an Apergerized, Rainman-esque “autistic-people-are-savants” portrayal, or a glossy “people-with-Asperger’s-are-quirky-but-they’re-just-like-everyone-else” feel-good portrayal. And, having watched it last night, I must say that there were a few implausible things I noted, but I could have been wrong about them. After all, Neil does not have Asperger’s. Some areas of his development have differed from the characteristics of AS. But these days, there are plenty of similarities.

In any case, this is not a review of Adam. This is a post about what happened when I decided to watch it. With Neil. Yes, I took a leap. I’ve been taking a lot of them lately, trusting that I’m doing the right thing. When I rented it, it was with the intention of watching it alone, but given Neil’s interest in relationships, I thought it might be good for him to see the film, and then we could discuss it and how it relates to him.

And discuss it we did. My son said so many profound things that I was constantly choking on my emotional reactions, trying not to let him see how his words affected me. With the movie, he took it all in. At times, such as when the two main characters were in bed together, he would avert his eyes, and I told him that it was a PG-13 movie, and I didn’t think we needed to be concerned about things going too far on film. Neil said, “It’s not that. I’m just afraid that he’s going to do or say the wrong thing and mess it up.” And I died inside, thinking of all the times in my son’s everyday life that he must feel that way about himself.

Neil noticed what difficulty Adam had in a restaurant, and that prompted a discussion about Neil’s own sensory issues. He remembered how hard it was for him to go into public restrooms because of the air hand driers. “They were like screaming banshees,” he said. And I pointed out that he learned how to filter that sound. “Yeah. They’re still loud, but I can handle them. It seems like Adam couldn’t handle the sounds in the restaurant,” Neil said, and I could hear some self-confidence (or was it relief?) in his voice that he had progressed to a point where he could handle being in a restaurant. And, Neil was quick to point out, he’s an extrovert who wants to do social things, whereas Adam is definitely an introvert and experiences much anxiety about doing those things. Neil may share the lack of social skills, but at least he is motivated to be social, and this made him feel good about himself. He also commented on a scene in which Adam becomes angry and does not deal with it well, raising his voice and throwing things. Neil said that sometimes anger feels like “a nuclear bomb going off” and “it’s so hard to control it.” But he also realized that he is learning to control it, and that, at fifteen, he is doing a better job of it than Adam.

A couple of areas really seemed to hit home with Neil. One was the focused talking about “specialist subjects.” For Adam, it was telescope facts and local theater history. For Neil, it’s a range of all his favorite movies, military history, and his favorite authors (Jules Verne and H.G. Wells). In this area, he is much like Adam—not realizing when he’s going on too long or noticing that he’s monologuing and the person is bored. Neil believes that he’s got this area under control because, in his social skills class, he’s learned to ask the person if he should continue talking about something. “And if they say ‘yes,’ I do.” But he doesn’t have the awareness to realize when he’s been talking too long and the other person is just being polite.

Also, Neil totally identified with the big picture social issues. “Normal people usually don’t get different people,” he’d say. Of course, many times I’ve said to him that different people are normal too, but that doesn’t seem to make sense to him. However, toward the end of the movie, he did say, “Eventually, people learn to understand people like . . . us.” I wasn’t sure if he hesitated because he was trying to remember Adam’s name, or if he was processing the fact that he identified with him. It’s been very hard for him in the past, although recently he’s felt better about it.

Overall, I’m glad I watched Adam with Neil. It’s true that seeing some of the behavior on film was hard for him, but I think that makes him more aware of it. If he knows what the challenges are, he can face them armed with that knowledge. In addition to that, seeing this movie prompted a discussion about the importance of jobs, and that if you get tired of doing your job after just two hours, you can’t say, “I’m done” and then leave. “I have to stay at the job so that I get the paycheck and can support myself,” Neil said. Halle-freakin-luiah! This understanding is a long time in coming. A long time. For years, he’d say that when he grew up he wanted to be an inventor of time machines and didn’t want to do any other job because it would bore him. I would suggest to him that he might need to do another job while he was inventing the time machine so that he would have money to pay for his food, etc., and this concept was completely lost on him. I don’t know what it was about watching Adam that changed his thinking, but it did, and I’m very glad. I think both of us are a little more optimistic about his future now. And that’s saying a lot about a movie I wasn’t sure I wanted to see in the first place.

Umbrellas for guests’ use in the lobby of the Hotel Country Villa, Nagarkot, Nepal, during monsoon season

Umbrellas for guests’ use in the lobby of the Hotel Country Villa, Nagarkot, Nepal, during monsoon season