[This post was originally published at Hopeful Parents]

Once upon a time there was a little boy who had autism. He did not start talking until he was five years old, and he often screamed and butted his head into people and walls to indicate his frustration. He also had agonizing sensory issues that made it impossible for him to filter loud noises, and he would scream and bolt whenever someone turned on a mechanical device in his presence. He would be disturbed by leaf blowers more than a block away, and the vacuum cleaner in the house was such an assault on his hearing that he would fly into a panic if anyone so much as walked in front of the closet in which it was kept. His parents would try to “sweep” the carpet as often as possible to avoid using the vacuum cleaner. When they absolutely needed to use it, one parent would take the little boy outside and comfort him while the other parent vacuumed.

After some time, the little boy’s parents divorced, and the mother would vacuum whenever he was visiting his father’s house. This went on for a few years, and then the father moved farther away, and the little boy could not visit him weekly. By this time the little boy had started learning to talk, and when it was time to vacuum, the mother would take him to his bedroom, show him how to cover his ears with a pillow, and shut his door while she quickly vacuumed.

It went on like that for several years. The mother would always notify her son before she would turn on the vacuum cleaner (as well as the blender, the food processor, and any other mechanical device in their home). The boy’s sensitive hearing still kept him most anxious about the vacuuming, and as his verbal skills increased, he would head to his room and admonish his mother, “Don’t start until my door is shut!” and call out “Is it over?” when the vacuum cleaner had stopped. By the time he was a teenager, the boy told his mother, “That vacuum is like shrieking banshees in my ear.” She thought it would always be that way, and sadly she wondered what other sounds in the world still tormented her son. He had gotten to a point where he could go to a movie theater if he wore ear plugs, but the vacuum cleaner still plagued him.

Then one day, after being in a series of situations involving loud noises and noting that her son was affected by them far less than he used to be, the mother decided to try something. She approached her son and mentioned that it seemed that his hearing wasn’t as sensitive as it used to be, and he said, matter-of-factly, “Well, I’ve just learned to deal with it.” She pointed out that he could now mow the lawn while wearing ear plugs, and she asked if he would be willing to try that with vacuuming. “Okay,” he said in his typically flat voice.

The mother gave him a brief tutorial on the vacuum cleaner, and, armed with his trusty ear plugs, the boy began to vacuum his bedroom while the mother went to work on something in another room. Amazed that he agreed to do it in the first place, she figured that he would do a quick job and shut the vacuum cleaner off as soon as possible. So when four minutes had gone by and the vacuum cleaner was still running in his room, she went back to check on things. She discovered that her son had put an attachment on the vacuum nozzle and was methodically detailing the corners of his room. She stood there, marveling at this unexpected turn of events. And then, with the ear plugs still firmly planted in his ears, her son looked up at her and smiled. The shrieking banshees no longer consumed him.

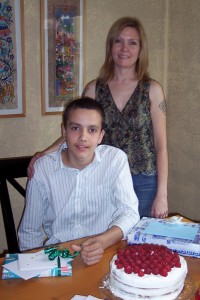

After the mother picked herself up off the floor, she praised him for taking the initiative and doing the extra work in the corners. She asked him how it went for him – vacuuming! – and he said in his flat but beautiful voice, “It was fine.” And even though it was a small thing, inconsequential in the grand scheme of things, the mother crossed “vacuum” off her mental list of things that her son, now almost sixteen, would “never” do and reminded herself that anything is possible. Anything.