When I started this blog in 2008, I had this vision of the post I would write when Neil graduated from high school. Obviously, I would write about how incredibly proud I was of him, how much he had taught me through the years, how consuming my love was for him, and how hopeful I was for his future. And I would post a short video of him receiving his diploma. I imagined that one of my relatives would be filming so that I could watch my son, who had always tried so hard, harder than anyone I know, and struggled so fiercely. I envisioned that the person filming would film me for a few seconds standing there, crying as I watched him, and when I noticed that they were filming me I would hide my face and wave them away, saying, “Film him, not me!” And the person would zoom in and film Neil, focusing on his beautiful, serious face, self-aware of his accomplishments and determined about his future.

*

All his life Neil has told me, whether through behavior or words and often both, what he needed. And I have learned to listen (and be attentive). He would tell me, by screaming and bolting, that a sound or an environment was too loud, too overwhelming, and he had to get out of there. He would tell me by rubbing his lips until all the skin around his mouth was red and cracked that his anxiety level was too high. And later, when he had the words to do so, he would beg me to homeschool him because mainstreaming was too torturous with the bullying he endured. After a year and a half of homeschooling, he would tell me that he wanted to try some medication that would help him to regulate his behavior so that he could go back to regular school, because he never stopped trying. A year later, he would tell me that he felt he had learned to regulate his behavior himself and that he no longer needed the medication. And he was right.

Two weeks ago, after a discussion about the dismal state of his grades and the fact that he is not aware of any executive function skills class that he is supposed to be in, he told me that he thinks he needs to get a modified diploma. His anxiety level has been so high that he has been pulling out his hair incessantly for weeks. He feels completely overwhelmed. And he is becoming aware of his emotional delay. Just a few weeks ago, at the grocery store, out of the blue he said, “I think the reason that I still like stuffed animals and Lego is because in my heart I’m like someone younger than myself.” I tried not to cry at his brave, self-aware statement and told him that I think he’s right, that his teachers and therapists have documented it over the years. I gently explained to him that at first they assessed him to have a six-year emotional delay, but somewhere along the way he gained a year, and so at age sixteen, he is like an eleven-year-old. “Yeah,” he said. I could see the wheels turning as he processed this.

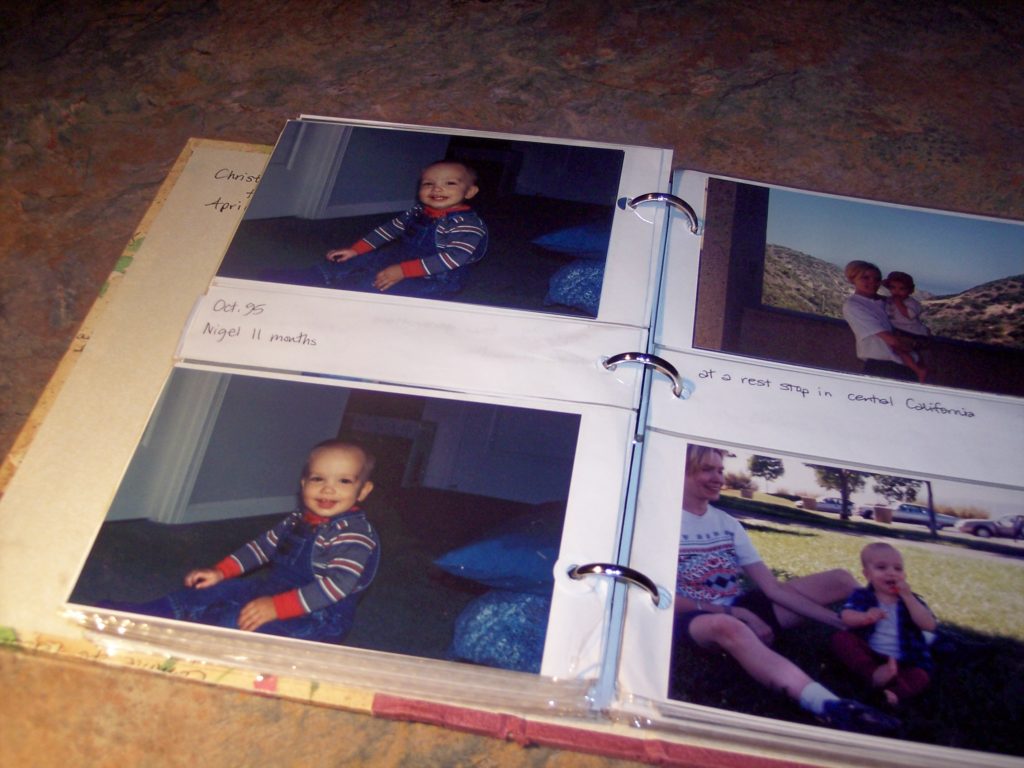

Here’s Neil at age eleven. How could I possibly expect this little boy to function as a high school sophomore? How could I think that the workload wouldn’t overwhelm him? That even though he was intelligent enough to understand it, he couldn’t handle the amount of it? Along with all of the social challenges and sensory issues he still battles on a constant basis? How could I think that the extensive support and assistance he receives both in and out of school would be enough? It’s not just about his lack of executive functioning. It’s about emotional maturity. How could I expect him to receive a regular diploma? That he would somehow figure it all out and navigate everything when he’s emotionally an eleven-year-old? How?

I’ll tell you how: Dreams. My son taught himself to read at age 3 ½, before he could even talk, and so I dared to dream. But don’t worry – I’m not throwing my dreams out the proverbial window just because he’ll be getting a modified diploma, because I now accept that that’s what he needs. I’ll still have dreams for my son, but those dreams are now realistically calibrated. What’s the problem with getting a modified diploma? It limits post-secondary educational opportunities, but with time and support perhaps in a few years we will be looking up online college degrees. And while I know that extended high school is a possibility for some students in similar situations, it’s not a good option for Neil. He’s comfortable at his high school, but he doesn’t want to be there any longer than necessary. He knows that option won’t work for him, and I agree.

No sooner had I indicated my support for his need to get on the modified diploma plan than he stopped pulling out his hair. I told him that it wouldn’t go into effect until everything had been written into his IEP at the upcoming meeting, and he understood. His relief, and his appreciation, was palpable. I had given him the autonomy to make a decision about his life and the respect and esteem that goes along with doing so. He knows himself. He knows what he needs. He always has.

*

For every bit of Neil’s progress over the years, I am truly grateful, and I am so proud of my son. But in all honesty it was painful for me to write this post. To know that after everything we’ve been through and all he’s accomplished, this is the best we can do. Mostly, it was painful for me to let go of a dream. Oh, I can say that I’ve “calibrated” my dream, but in reality, I had to let it go. And that’s okay. Because I’ve learned that my dreams for him are not necessarily his dreams for himself. And the fact is, when I look ahead to his graduation two and a half years from now, the particulars of his diploma will be different, but nothing else will. Someone will still be videoing it, I’ll still be crying, and I’ll still feel all the things that I would have felt had he received a regular diploma. I’m certain of that. And I’m certain that Neil’s beautiful, serious face will still reflect the awareness of his accomplishments, and his determination for the future.

I’m sure we’ve all done it at some point. We look through the photo albums, gaze at the images of our little ones and sit there, transfixed, in memory. We wonder – that thing he’s doing with clenching his fists – did that somehow point to autism? How he used to put his head back and say ‘aaahhh’ repetitively? The way he did the ‘5-point crawl,’ with his forehead on the floor? We just thought it was cute at the time, endearing. But he laughed! He smiled!

I’m sure we’ve all done it at some point. We look through the photo albums, gaze at the images of our little ones and sit there, transfixed, in memory. We wonder – that thing he’s doing with clenching his fists – did that somehow point to autism? How he used to put his head back and say ‘aaahhh’ repetitively? The way he did the ‘5-point crawl,’ with his forehead on the floor? We just thought it was cute at the time, endearing. But he laughed! He smiled!