Often over the years I’ve had relatives and friends ask me what my stand is on the vaccine/thimerosol issue. I’ve devised my own theory.

I believe that thimerosol is partly responsible for some cases of autism. What I emphatically believe is that in the last thirty years, large amounts of chemical toxins in our environment (including our food, air, and water) are contributing (not causing, but contributing) to the increase of autism cases, along with increased awareness for diagnosing the milder cases. Thimerosol in vaccines is included on my list of chemical toxins. But I certainly don’t believe that all cases of autism were caused by thimerosol.

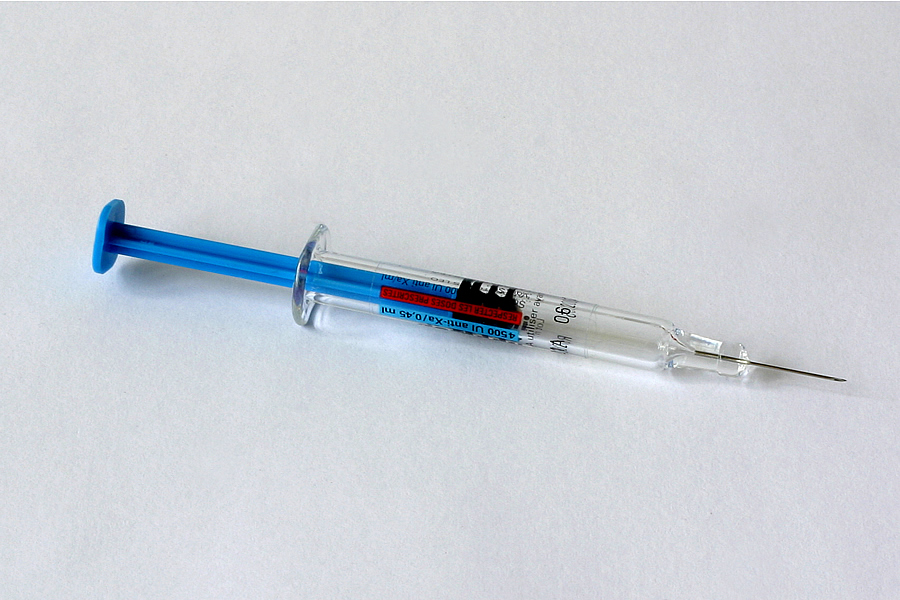

When I was six months pregnant with Neil, I experienced pre-term labor and was hospitalized while I received terbutaline intravenously. I have often wondered if the presence of this chemical affected Neil’s development in utero. I believe he was genetically predisposed to autism, and the introduction of harsh chemicals through medication I received as well as the aggressive inoculation program thrust upon him after birth caused him to develop autism. It was the combination, not just one or the other.

Hence the variance of the spectrum. I think this theory also helps to explain why some children who are significantly impacted by autism can, with therapy, progress to a point of being less severe in some areas, while others do not. It also explains why some autistic individuals respond so well to GF/CF diets, while others do not. Autism manifests itself differently in each individual because there are so many different causes and contributing factors.

I hope I live to see the day when we understand more of the complexities of autism, and maybe have some concrete answers. But for now I’ll have to be satisfied with my own interpretations, which will more than likely continue to evolve. What are yours?

Image credit: Christophe Libert