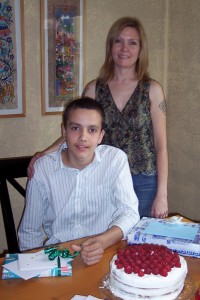

Last weekend, Nigel had some friends spend the night for a little end-of-the-school-year party. I’ve mentioned Nigel’s friends, Nicholas and Tyler, before; Nicholas is Nigel’s age and Tyler is Aidan’s age. They are also brothers who are involved with Scouts, and we’ve been fortunate to know their family for several years. They’ve always been supportive and understanding of Nigel. I know that he values their friendship greatly, as do I.

So the boys had a blast, complete with pizza, root beer floats, gun fights, and a movie marathon. They’ll indulge Nigel in watching his latest favorite disaster movie with him, and he doesn’t mind if they fall asleep while they do. They’ve seen Nigel melt down, they’ve witnessed him being harassed at school, they know he’s prone to movie echolalia, used to have a type of barking laugh, and can sometimes get a little carried away when he’s having fun. They also know that sometimes he says things that are inappropriate or negative, and they realize that he doesn’t always understand these things. They’ve seen him at his worst, but they’ve also seen him at his best – creative, fun-loving, imaginative, and knowledgeable. I, for one, am so appreciative that they’ve stuck around. I know that Nigel is too.

And I appreciate their parents just as much. Their mom, Cheryl, a very good friend and a regular commenter here, and I like to talk for a bit during the pick-up/drop-off times when we can. We check in about our lives – our kids, parents, pets, homes, jobs, plans. Last weekend we talked about the upcoming transition to high school, that we couldn’t believe how big our older sons have so suddenly become. I talked about how much better I feel about how Nigel’s doing socially, how the combination of his medication and having a few good kids around him has helped immensely. I mentioned that I thought it really made an impression on most of the other kids that I had to pull him out to homeschool him for a year and a half, and when he came back, many of them realized – hey, this is someone who needs a little extra help, a little understanding. Maybe those kids even matured a bit. Cheryl told me that she had recently asked Nicholas how Nigel was doing at school, if anyone was bothering him. Nicholas told her that aside from a small group of kids that likes to target him, everyone else has been nice to him. He said that if anyone sees any of that group approach Nigel to bother him, someone else always goes over to intervene and help Nigel out. They’ve got his back.

I told Cheryl how glad I was to hear that, and if, in my choked-up state, I neglected to thank her, I’m doing it now. Her boys, and a few others, have always been the core of Nigel’s circle. A few months ago, when Nigel, by choice, started back at the middle school to finish eighth grade, I tried to form a Circle of Friends by requesting it at his IEP meeting, talking to the principal about it, and emailing information to those who could make it happen. Despite my efforts, the administration didn’t pursue it. I felt so bad, felt that I should have done more, been a squeakier wheel.

But something did happen. When I wrote the letter to the school administrators, they talked to the kids who were involved in making a spectacle of Nigel. They – finally – told the kids a little about autism. And some of those kids felt remorse, and concern. And instead of continuing to have fun at his expense, many of them changed. They started being kind and helping him. I had read that this can be a positive result of Circle of Friends programs – that even kids who are not involved in the program hear about it and respond to the autistic students differently than they had before. It’s a ripple effect that can sometimes reach the whole school. That is what I hoped for when I requested a Circle of Friends program at Nigel’s school. And even though the program was never officially started, it seemed to happen on its own.

Less than a year ago, Nigel sat in his room one night and drew ape faces in his yearbook on the photos of all the kids that had bullied him. It made him feel better – his own type of art therapy. It was heartbreaking to see how many faces he drew over. This week, when he came home with his yearbook, it was filled with autographs and well-wishes for a good summer. It was filled with “you’re cool” and “see you next year.” These kids will be going with him to the local high school in September.

I had wanted a Circle for Nigel, but in less than three months, I got something much bigger. And I have a feeling that we’ll be having a lot more pizza-and-movie parties at our house next year.