My younger son Adam, who is twelve, has recently discovered Bob Marley. He found one of my CDs from my college days (when I first discovered Bob) and it was love at first listen. Adam plays it day and night. He tells me that he likes the music, but also the lyrics. And I’ve noticed that, too. Adam seems even calmer and more introspective than usual. What I hadn’t noticed was that Neil had also started listening.

Last weekend the boys were very excited because The Day the Earth Stood Still was opening. They had recently seen the original and looked forward to comparing the new one to it. I told them that we’d wait until the following weekend so it wouldn’t be so crowded. Then I made the fatal mistake of writing on the calendar the day and time I hoped that I could take them to see it. If it’s on the calendar, it’s in stone as far as Neil is concerned. It’s going to happen. And usually, it does. But that morning the schools had scheduled an emergency 2-hour late start due to bad road conditions, and that threw everything off for the day. Because Adam started school two hours later, I couldn’t go into work until two hours later. Consequently, I didn’t finish my work until two hours later than I normally do. By the time I got home, I could not do all I needed to do in time to go to the movies that evening, and we would go the following day, I announced.

Neil got upset. “But it’s on the calendar!” he yelled and began breathing heavily through clenched teeth, eyes wild as he quickly went into meltdown mode. This was not good. I had plans with a friend later that evening (something I had planned to do after the movie), and if Neil didn’t calm down, I wouldn’t be able to leave him. I tried reminding him about “Old Plan, New Plan.” “That doesn’t work!” he yelled. He then took a wooden ruler and mutilated a piece of pizza with it. I could tell he was escalating. He went to the living room and broke one of my hand-painted pysanky eggs from relatives in Slovakia. I knew that my response was crucial – he wanted a reaction out of me, so I did not react. I calmly said, “Neil, pick up those broken pieces and put them in the trash.” And I think he was a little surprised that I didn’t yell at him about the egg, so he actually cleaned it up. He resumed his verbal tirade, but at least he stopped being destructive. Then I had an idea. An alternative for him. It was a “New Plan,” but I didn’t want to call it that.

It was risky, because I didn’t want him to think that I was rewarding him for his behavior. But what I hoped to accomplish was to help motivate him to regulate his behavior himself. Some would call it a bribe. But God knows that when you have to change plans on an autistic teen, you better have an acceptable back-up plan.

I sat him down and tried to look into his wild eyes. “Neil, here are your choices. You can be mad about not going to see the movie tonight, but that’s not going to make it happen. Or, you can calm down and come with me to the store to pick out a video rental and get some ice cream, and we’ll see The Day the Earth Stood Still tomorrow.” Then I got up and went to my room to get my boots and coat.

Adam followed me into my room. He looked at me. “Why does he act that way?” he asked with concern and sadness in his voice. “Honey, it’s because the autism makes it hard for him to regulate his emotions and his behavior.”

“Then how is he going to take care of himself when he’s an adult?” Adam asked in a sincere voice.

A chill ran through my body. I looked at him. “We don’t know if he will. But he’s learning; he’s trying. I think he’ll figure it out. And he can live with me as long as he needs to. So can you.”

I put my arm around him and we walked out into the hallway. Neil was standing by the front door, with his shoes and coat on. I looked at his face, and the wildness was gone, replaced by a look that I couldn’t determine. Remorse? Gratitude? Maybe both. “I’m ready,” he said. “Okay, I’ll get my purse and keys,” I said. As I walked off, I heard Adam quietly say to him, “I’m glad you were able to calm down.” And my heart filled with far too many emotions to identify.

A moment later, as I started the car, Neil asked from the back seat, “Can we listen to ‘Don’t Worry About a Thing’?”

“It’s called ‘Three Little Birds,'” Adam said.

“Sure,” I said, inserting the CD. And then we all sang, even Neil:

Don’t worry . . . about a thing . . . ‘cause every little thing . . . gonna be all right . . .

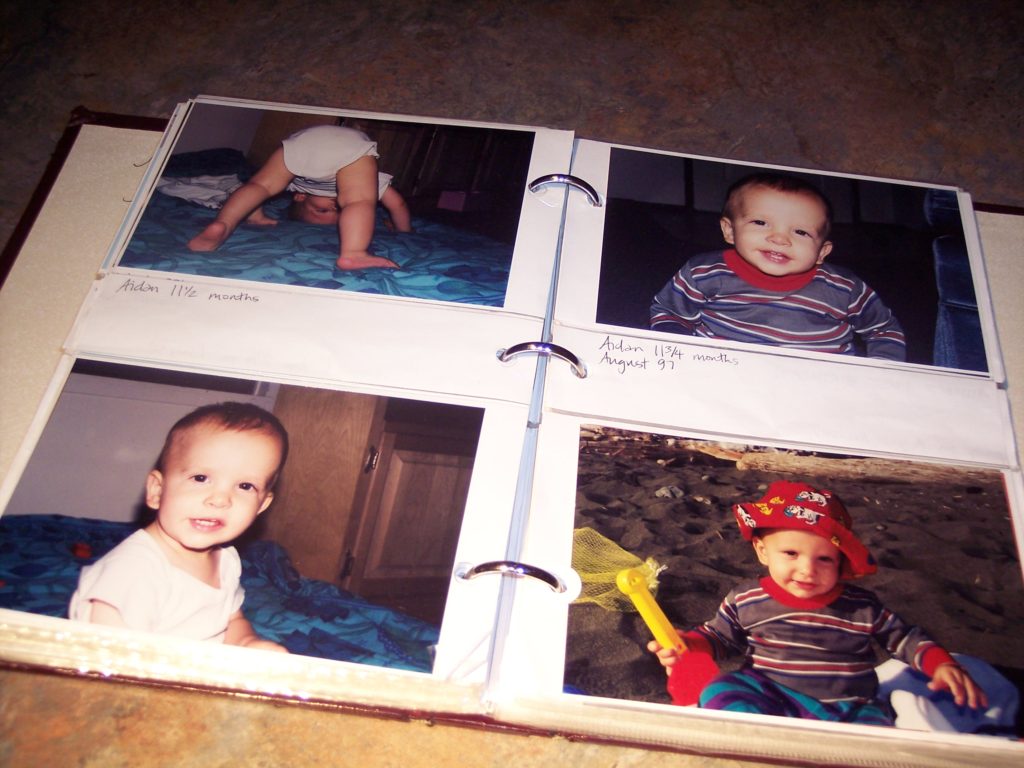

Even though he’s wearing his brother’s shirt 😉

Even though he’s wearing his brother’s shirt 😉